Yale’s engagement with the Near East began in the early years of the College. In accordance with the tenets of New England Calvinism and the trilingual ideal of the Renaissance, biblical Hebrew was a required subject in the mid-eighteenth century, but was only taught sporadically. Ezra Stiles (BA 1746), President of the College from 1778 to 1795, developed a strong interest in biblical Hebrew and Jewish mysticism, and attempted to reintroduce biblical Hebrew into the College curriculum; his course was the first at Yale to be given grades, most of which were failing. He also taught himself to read Arabic prose. Stiles’ successor, Timothy Dwight (BA 1769), made a professorship in Oriental Languages one of his three major priorities for rebuilding the College, but the first appointee, Ebenezer Marsh, died young and was replaced by a Classicist, James Luce Kingsley (BA 1799). With the formation of the Yale Divinity School in 1822, Hebrew was offered by Josiah Gibbs (BA 1809), best remembered today for his role in the Amistad affair, in which he succeeded in establishing communication with the captives. He was Yale’s leading philologist in his generation, associate of Noah Webster (BA 1778), and an early proponent of introducing German linguistic scholarship to the United States.

Gibbs inspired his student, Edward Salisbury (BA 1832), to take up the study of Arabic and Sanskrit, the defining “Oriental languages” of his time, on the basis of the long-standing European interest in Arabic and the European discovery of Sanskrit and Persian in the late eighteenth century. Salisbury therefore studied Arabic in Paris with A. I. Silvestre de Sacy and in Bonn with de Sacy’s student, Georg Freytag, and mastered Sanskrit as well at Paris and Berlin, where he attended the lectures of Franz Bopp. He returned to Yale to hold America’s first graduate professorship and to offer America’s first formal courses in Arabic and Sanskrit. Determined to create a discipline of Oriental Studies in the United States, Salisbury was a key figure in building the American Oriental Society: he edited, paid for, and largely wrote the first numbers of its Journal, and purchased books, periodicals, and manuscripts to build up an Oriental collection in the Yale library. Salisbury’s most distinguished student, William Dwight Whitney, was America’s pre-eminent Sanskritist and linguist of the second half of the nineteenth century, but had little interest in Near Eastern languages, so Arabic disappeared from the curriculum and Hebrew remained a Divinity School subject.

Gibbs inspired his student, Edward Salisbury (BA 1832), to take up the study of Arabic and Sanskrit, the defining “Oriental languages” of his time, on the basis of the long-standing European interest in Arabic and the European discovery of Sanskrit and Persian in the late eighteenth century. Salisbury therefore studied Arabic in Paris with A. I. Silvestre de Sacy and in Bonn with de Sacy’s student, Georg Freytag, and mastered Sanskrit as well at Paris and Berlin, where he attended the lectures of Franz Bopp. He returned to Yale to hold America’s first graduate professorship and to offer America’s first formal courses in Arabic and Sanskrit. Determined to create a discipline of Oriental Studies in the United States, Salisbury was a key figure in building the American Oriental Society: he edited, paid for, and largely wrote the first numbers of its Journal, and purchased books, periodicals, and manuscripts to build up an Oriental collection in the Yale library. Salisbury’s most distinguished student, William Dwight Whitney, was America’s pre-eminent Sanskritist and linguist of the second half of the nineteenth century, but had little interest in Near Eastern languages, so Arabic disappeared from the curriculum and Hebrew remained a Divinity School subject.

“The Legacy of Arabic in America” by Piney Kesting, Amaroco World, January/February 2018

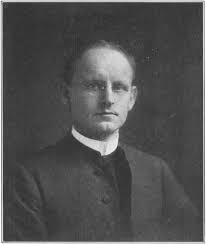

This changed dramatically with the appointment of William Rainey Harper (Ph.D. 1875), who had studied linguistics with Whitney, as Professor of Semitic Languages in 1886, the effective beginning of the present Department. Harper, an extraordinarily charismatic figure, rapidly became one of Yale’s most popular teachers. He reinvigorated the teaching of Hebrew to the extent that it was said New Haven policemen memorized Hebrew verb forms as they walked their beats. In tandem with his brother, Robert Francis Harper, he brought biblical Hebrew, Classical Arabic, Babylonian, Aramaic, and Egyptian into the new Yale Graduate School, and students flocked to his classes. Between 1886 and 1891, when the Harpers left for the University of Chicago, eighteen students received doctorates in Aramaic, Assyriology, Bible, and Hebrew, twelve in 1891 alone, a record that holds today.

Harper’s biblical program was carried forward at Yale by his student, Frank Knight Sanders (Ph.D. 1889), along with Charles Foster Kent, who between them produced a staggering number of publications on biblical subjects, Kent alone over 150 titles and editions. But these, though based in philology, were intended for readers of the Bible in English; the majority of doctorates taken under their supervision were biblical in nature. Recognizing the need for a first-rate Semitic philologist, Sanders invited a young faculty member from Andover Theological Seminary, Charles C. Torrey, to Yale in 1899, a decisive moment in the evolution of the Department.

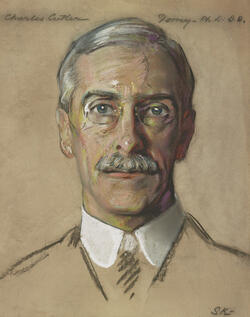

Torrey had studied Arabic and other Semitic languages with Theodor Nöldeke, Julius Euting, and Peter Jensen at Strasburg. He had taken his German doctorate in Koranic studies but was highly proficient in biblical scholarship of all periods as well, noted for his controversial dating of post-Exilic biblical books and insistence that the Gospel accounts were translations from Aramaic. He produced the first major Arabic text publication in the United States, an edition of Ibn Abd al-Hakam’s account of the conquest of Egypt (1922), and published other Arabic texts as well. Torrey was the founding Director of the American School of Oriental Research in Jerusalem (1900) and one of its guiding spirits for the next quarter century. As long-time editor of the Journal of the American Oriental Society, he saw to a diversification of its subject matter and improvement of its quality. He also persuaded the University to acquire an important collection of Arabic manuscripts to improve the situation with American Arabic studies, which hitherto had depended on access to European collections to do original work. When Yale underwent a reorganization, beginning in 1919, a new department, Religion, later Religious Studies, soon took over undergraduate instruction in the English Bible, and the present Department, under the name of Semitic and Biblical Languages and Literatures, continued to teach ancient Near Eastern languages on the Graduate level; Torrey served in both departments as well as the Divinity School.

Torrey had studied Arabic and other Semitic languages with Theodor Nöldeke, Julius Euting, and Peter Jensen at Strasburg. He had taken his German doctorate in Koranic studies but was highly proficient in biblical scholarship of all periods as well, noted for his controversial dating of post-Exilic biblical books and insistence that the Gospel accounts were translations from Aramaic. He produced the first major Arabic text publication in the United States, an edition of Ibn Abd al-Hakam’s account of the conquest of Egypt (1922), and published other Arabic texts as well. Torrey was the founding Director of the American School of Oriental Research in Jerusalem (1900) and one of its guiding spirits for the next quarter century. As long-time editor of the Journal of the American Oriental Society, he saw to a diversification of its subject matter and improvement of its quality. He also persuaded the University to acquire an important collection of Arabic manuscripts to improve the situation with American Arabic studies, which hitherto had depended on access to European collections to do original work. When Yale underwent a reorganization, beginning in 1919, a new department, Religion, later Religious Studies, soon took over undergraduate instruction in the English Bible, and the present Department, under the name of Semitic and Biblical Languages and Literatures, continued to teach ancient Near Eastern languages on the Graduate level; Torrey served in both departments as well as the Divinity School.

In 1910, J. Pierpont Morgan presented Yale with a fund to create a professorship in Assyriology, as well as a Babylonian Collection, of which the professor was also Curator. The first incumbent, Albert T. Clay, soon established Yale as a leading center for Assyriology, building up the largest collection of cuneiform tablets and other Mesopotamian artifacts in America, training numerous students, and founding three publication series. He was a superb epigrapher in all periods of cuneiform writing, author of twelve volumes of cuneiform texts, and expected his students to do the same. Clay was the founder of the Baghdad School of the American Schools of Oriental Research and served as the Schools’ Professor in Jerusalem in the crucial years 1919-1920 when the futures of both Iraq and Palestine were hanging in the balance. There he founded the Palestine Oriental Society, forerunner to the present Israel Academy of Arts and Sciences. He was also instrumental in laying the foundations for Judaic Studies at Yale, eliciting the first offer of a professorship in that area, and securing a superb collection of Judaica assembled by George Kohut for the University Library.

In 1910, J. Pierpont Morgan presented Yale with a fund to create a professorship in Assyriology, as well as a Babylonian Collection, of which the professor was also Curator. The first incumbent, Albert T. Clay, soon established Yale as a leading center for Assyriology, building up the largest collection of cuneiform tablets and other Mesopotamian artifacts in America, training numerous students, and founding three publication series. He was a superb epigrapher in all periods of cuneiform writing, author of twelve volumes of cuneiform texts, and expected his students to do the same. Clay was the founder of the Baghdad School of the American Schools of Oriental Research and served as the Schools’ Professor in Jerusalem in the crucial years 1919-1920 when the futures of both Iraq and Palestine were hanging in the balance. There he founded the Palestine Oriental Society, forerunner to the present Israel Academy of Arts and Sciences. He was also instrumental in laying the foundations for Judaic Studies at Yale, eliciting the first offer of a professorship in that area, and securing a superb collection of Judaica assembled by George Kohut for the University Library.

At Clay’s premature death in 1925, Torrey, and Clay’s successor, Raymond Dougherty, successfully urged the continuance of independent staffing for the Babylonian Collection, first with Ettalene Grice (Ph.D. 1917) and then with Ferris Stephens (Ph.D. 1925); the latter was to serve both the Department and the Collection, as well as the American Oriental Society, until his retirement in 1962.

If most of the graduate students who took their doctorates in the Department between 1888 and 1920 were Protestant ministers, after 1920 the graduate student population diversified, to include Reform and Orthodox Jewish immigrants from Russia, Poland, Lithuania, and Palestine, and its first African American, William Yancy Bell (Ph.D. 1924).

The Department granted its first doctorate to a woman, Sara A. Emerson (Ph.D. 1903); by the late 1960s women gradually made up about half the graduate student population.

The Department went through a crisis in 1933 with the retirement of Torrey and the untimely death of Clay’s successor, Raymond Dougherty. The outcome was the appointment of Albrecht Goetze, who had been dismissed from his professorship at Marburg as “politically unreliable” in 1933, as Professor of Assyriology, and Julian Obermann as Professor of Semitics. Goetze’s early training and doctorate were in linguistics, but with the decipherment of Hittite he became a leading scholar in that discipline. At Yale, he carried on with both Hittite and Assyriology and was a towering and productive figure in both these fields until his death in 1971, as well as founding editor of the Journal of Cuneiform Studies. Obermann founded new series, the Yale Judaica, devoted to the publication and translation of major works of Jewish intellectual history, to which he contributed the first two volumes.

In 1935, the Department was incorporated into a new entity called, after the fashion of the time, “Oriental Studies.” American foundations, especially the Ford Foundation, and the American Council of Learned Societies, had been calling for reform of American college curricula to include more world languages and more emphasis on the contemporary forms of languages, such as Arabic and Persian, which were then taught only in their classical forms. The outbreak of the Second World War gave new impetus to this drive, so Oriental Studies at Yale included Chinese, Japanese, Malay, and Russian, as well as spoken Egyptian Arabic.

In 1946, Oriental Studies broke into three departments, of which Near Eastern Languages and Literatures (the old Semitics Department under a new name), came under the energetic the leadership of Carl Kraeling, of the Divinity School. The Department therefore remained as it had been, a small, very high-quality program dedicated to the ancient and medieval Near East on the graduate level. Key faculty members included, among others, Millar Burrows, best known for his involvement with the American Schools in Jerusalem, and as a leader in the publication of the Dead Sea Scrolls; Marvin Pope, best known for his work in Ugaritic religion and for his translations of the Song of Songs and Job; and Harald Ingholt, a specialist in the archaeology of Syria-Palestine and Gandaran art.

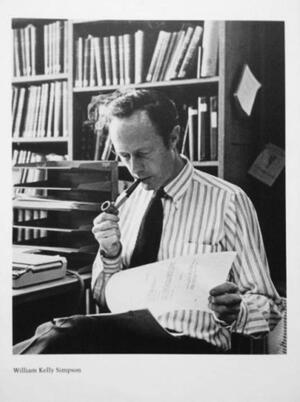

Egyptology began at Yale with the part-time appointment of Ludlow Bull (’07), of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in 1924. Bull built up a collection of Egyptian art at Yale and taught courses as needed. The first degree in Egyptology was awarded in 1942; the second was in 1954, to William Kelly Simpson (’47). At Bull’s death in that year, the Department appointed Henry Fischer, succeeded by Simpson in 1958.

Simpson’s combination of art-historical connoisseurship, first-rate philology, and archaeological field experience made Yale for the first time a world center for Egyptology. His publications of the Naga ed-Deir texts, his classic anthology of Egyptian literature in translation, his work in Nubia and on the publication of the Giza mastabas, his involvement with the raising of the great figures at Abu Simbel, and his curatorship at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts were representative of his many interests. Robert Ritner joined the program as a second Egyptologist in 1991. Bentley Layton inaugurated a degree program in Coptic in the Department in 1983.

Simpson’s combination of art-historical connoisseurship, first-rate philology, and archaeological field experience made Yale for the first time a world center for Egyptology. His publications of the Naga ed-Deir texts, his classic anthology of Egyptian literature in translation, his work in Nubia and on the publication of the Giza mastabas, his involvement with the raising of the great figures at Abu Simbel, and his curatorship at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts were representative of his many interests. Robert Ritner joined the program as a second Egyptologist in 1991. Bentley Layton inaugurated a degree program in Coptic in the Department in 1983.

Arabic Studies at Yale began a brilliant new phase with the appointment of Franz Rosenthal in 1956. His prodigious scholarly output included studies of Palmyrene and Aramaic, and numerous studies of Arab-Islamic civilization, including monographs on autobiography, historiography, the Classical heritage in Arabic, humor, gambling, knowledge, and drug use, as well as a three-volume translation of the Muqaddimah of Ibn Khaldun. Joel Kramer (Ph.D. 1967) then Dimitri Gutas joined the program as second Arabists under his aegis (1967, 1976).

The Department’s involvement with archaeology in the Near East began with Torrey’s excavations at Sidon (1900). Clay hoped for an expedition to Larsa or Uruk, but these did not materialize. Department faculty participated in the work and publication of the Jerash (Kraeling) and Dura Europos (Ingholt) projects, as well as Nippur (Goetze), and Toshka and Arminna in Nubia (Simpson). The Department’s first full-time appointment in archaeology was Richard Ellis (1964), succeeded by Harvey Weiss (1973), who directed excavations at Tell Leilan (ancient Shubat-Enlil) in Syria, beginning in 1979.

Assyriology flourished in the 1960s and 1970s with William W. Hallo (1962) and Jacob J. Finkelstein (1965), supported by Harry Hoffner (1969). Hallo’s numerous publications spanned Sumerian and Akkadian, Biblical and Judaic Studies, and Near Eastern history; forty-five of his essays on Sumerian culture alone were republished in The World’s Oldest Literature (2010). His three-volume anthology, The Context of Scripture (1997-2002), demonstrated his interest in comparative study, his translation of Franz Rosenzweig’s The Star of Redemption (1971) his scholarly commitment to Judaism. Finkelstein’s research interests lay in Old Babylonian documents, cuneiform law, and Mesopotamian intellectual culture. Characteristic of his broad research interests was his long-term project “The Goring Ox,” a study of the legal principle of “deodand” from antiquity to modern American jurisprudence, portions of which were published after his untimely death. Hoffner, best known as a Hittitologist, carried forward Yale’s tradition in that field, and taught other languages as well, including Akkadian and Egyptian. Asger Aaboe, jointly appointed with History of Science (1961), taught Mesopotamian mathematics and astronomy.